Return

to Paleontologoy Archives

MARINE FOSSILS OF ORANGE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA

THE ORANGE COUNTY GEOLOGICAL

COLUMN

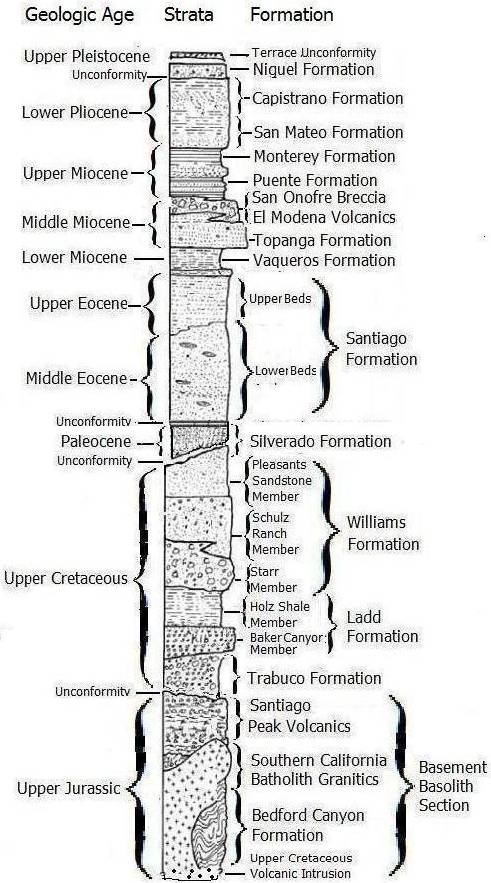

Orange

County’s geologic history, as shown in the geologic column, begins in the Upper

Jurassic Period of the Mesozoic.

As the column illustrates, the stratigraphic record of Orange County is

a complex and fascinating succession of environments and volcanic events from

the age of the dinosaurs right up to the present landscape, which offers a rich

historical tradition too. Each

formation in Orange County, and the world at large, is differentiated from

strata above or beneath them by physical characteristics (color, grain size,

rock type, and thickness). The

first division within the greater scheme is called a formation. If there is further division within the

strata it is called a member.

Abnormalities, such as faults and volcanic intrusions, disrupt the

normal flow of stratification.

Missing layers or periods, which are called unconformities, shown in the

column below, add an element of mystery to the science. In the subsequent figure, the

pattern of geological or stratigraphic progression is likewise uneven, and, as

with all such geologic columns, the record remains far from perfect. Paleontologists often blame erosion or

lack of deposits for these missing strata. While such causes might be easily explained, lack of

sedimentary deposit is not understood unless the underlying and overlying

strata are known to be marine or terrestrial rock. In the case of terrestrial strata or the lack thereof, the

retreat of the sea and a dry landscape easily explains the lack of sedimentary

deposits set down by fresh or salt water, which might contain fossils. For the geological history and strata

shown in the geological column, these gaps are evident, and yet those layers of

sedimentary rock, constituting the Holz and Baker Members of the Ladd

Formations of Orange County, California, make up for this lack with a diverse

record of marine invertebrates and sharks’ teeth.

The oldest formation in the column is the Bedford

Canyon Formation, which was laid down during the Upper Jurassic period. Like almost all the other formations on

the column, it’s a marine deposit, composed mostly of thin, graded sandstone

that alternates with shale, which paleontologists believe are deep-sea fan

deposits called turbidites (sediments deposited by turbidity currents). As indicated in the column, Bedford

Canyon Formation is highly deformed (by faults and uplifts) and the successive

layering within the formation actually indicate inverted superposition, which

reflects major a tectonic event during the Upper Jurassic. Calcareous fossils of mollusks and

brachiopods are rare in this formation, occurring mainly in local pods and

lenses of limestone. The age of

the Bedford Canyon Formation is estimated to be 140 to 120 Million years old

(Upper Jurassic to Middle Cretaceous).

Overlying as well as intruding into Bedford Canyon’s rocks, as indicated

in the figure, is igneous strata called the Santiago Peak Volcanics. Also intruding into the Bedford Canyon

Formation is the Southern California Batholith Granitics (also called the

Peninsular Ranges Batholith), which is an important intrusive event along the

entire west coast of North America dated at 120 to 90 Million years ago. As illustrated, the three

formations—Bedford (sedimentary), Santiago (igneous), and Peninsular

(metamophic), which represent the three major types of rock—are called the

Basement Basolith Section. They

are, in fact, the foundation or basement of the Santa Ana Mountains of Orange

County, California.

Overlying the basement formations is perhaps the

most important portion of our geologic column, at least for the fossil

collectors like myself. Here is

recorded a massive marine layer between the Trabuco Formation and Pleasants

Sandstone Member of the Silverado Formation, in which is found the most

fossiliferous zone in Orange County: the Holz Member of the Ladd

Formation. This member, along with

the slightly older Baker Member has been assigned either a Middle or Upper

Cretaceous age. Since the latest

research cites the more recent date, I shall identify the Ladd Formation as

Upper Cretaceous. Henceforth, for

that matter, I shall the follow the lead of current paleontology and call

Ladd’s important member the “Holz Shale.”

This formation begins on top of the Trabuco Formation, an iron-oxide

conglomerate of gravel, constituting an alluvial fan deposited along the foot,

above the basement, of the ancient Santa Ana Mountains. The Trabuco Formation begins on one of

those mysterious unconformities, probably caused by erosion. The cobblestones and boulders within

this formation, however, were evidently provided by the weathering and erosion

of older formations. Of course,

this essentially terrestrial, alluvial fan environment make it more interesting

to the geologist than the paleontologist or collector. One of those most significant divisions

overlying the Trabuco formation, from the standpoint of fossil-collecting, is

the Ladd Formation, consisting of both basal conglomerate and sandstone in the

Baker Canyon Member and above this strata the Holz Shale Member in which I

found my marine fossils and sharks’ teeth. The Baker Canyon Member, itself, represents a

transition from coastal braided stream sand and gravel to shallow marine shore

face sandy deposits that contain an abundance of shallow marine invertebrates,

mostly mollusks. The Holz Shale

represents a shallow-to-deep marine shelf and slope deposit that is rich in

fossils in its lower level. I

discovered abundant and diverse mollusks in the shale bed, including ammonites. I also found several sharks teeth. Above the Holz Member and the overlying

Williams Formation and Pleasants Member lies the Silverado Formation,

sedimentary rock lying within the Paleocene Epoch. One single sample, represented in my collection containing

turritellas is shown in a subsequent sequence, was found in the Silverado Creek

below. The matrix of the rock and

its fossils, which are comparable to this layer overlying the Upper Cretaceous

Williams Formation and Pleasants Member, are quite different than the Holz and

Baker shale.

With the depositing of the Silverado Formation, a

relatively short period of geologic time, we are brought to the Tertiary Age

and the boundary between the two great eras in the geologic time scale—the

Mesozoic (Age of Reptiles) and Cenozoic (Age of Mammals), two labels which

overlook a vast assortment of animal and plants not covered in these

titles. The very boundary where

the Silverado Formation begins and Williams Formation ends, as shown in the

column, fittingly enough exhibits an unconformity. The basal Tertiary deposits, beginning with the

Silverado Formation, though terrestrial in their extent, reportedly exhibit a

few invertebrates (indicating a delta and bay near landfall), such as oysters

and turritellas, and a few vertebrate fossils, that had evidently washed into

the mix. Above the Silverado

Formation, are several formations, most of whom are outside of this

discussion. (A compilation of

California paleontological sites, including the location, age, period, and

fossils found in these locations is given in this list.) An interesting anomaly for me were the

two samples of petrified wood I found in Villa Park, California, not far from

Silverado Canyon and the Ladd and Williams Formations. According to a recent discovery in Orange

County, there were also dinosaurs in this area. The Upper Cretaceous zone in which invertebrates are

abundant has yielded both plant and vertebrate fossils, which include the

fossil remains of a hadrosaur, so it’s not so strange to find petrified

wood. The scenario given for this

geological province is typical for many Late Cretaceous locations: a shallow

sea, surrounding by hills and marshes, a condition that remained in Orange

County, California, when the Paleocene Epoch ushered in the Age of Mammals.

The next layers of sedimentary rock, which I

explored in Orange County, were the Upper Miocene Monterey Shale of South

Laguna Beach and Upper Pliocene Capistrano Formation of Newport Beach, California,

which are at the limit of my exploration of the geologic column. Above this limit, out the range of the

Orange County Geological Column, the ancient sea fully retreated. During the Pleistocene Epoch, a heavily

vegetated, marshy forest extended beyond the shoreline, and in a primarily

terrestrial environment, typical Ice Age mammals roamed the new world.

Mollusks,

Sharks Teeth, and Worm Borrows from the Holz Shale and silverado formation

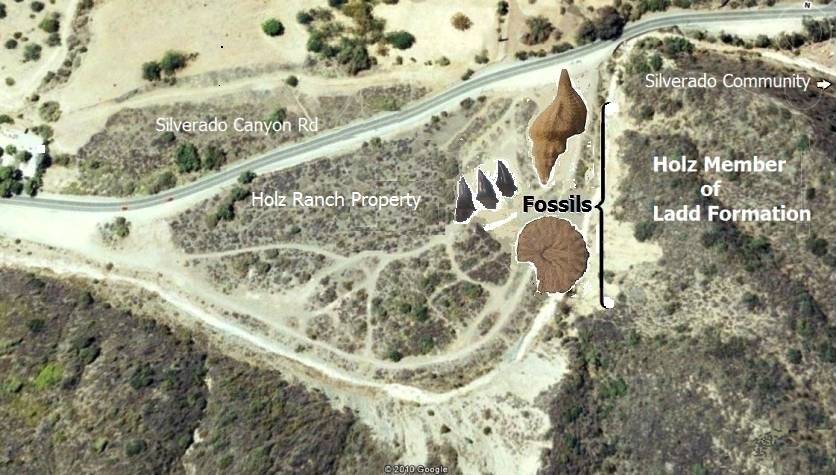

Several years ago I obtained permission from the Holz family to search for fossils on their land. This site exposes the Upper Cretaceous Ladd Formation of Orange County in the main outcrop and a Paleocene rim that I took a few samples from (primarily turritellas). The eccentric residents of Silverado Canyon were curious and, at times, hostile to my presence. One woman destroyed the bridge of dead limbs I had made to cross over the stream, even when I explained that I had permission to be in this desolate place. A sign read “No Trespassing” by the road, and I was forced to present my letter each time the police or pedestrians challenged me as I prospected along Silverado Creek. During the many months I searched for fossils in the Holz Shale, I found ammonites, gastropods, bivalves, and a few sharks teeth. The assemblage below lists both the scientific name and the common name for each genus and species. Alongside this fossil collection is a stream worn slab of turritellas, most likely belonging to the Early Paleocene (Silverado Formation). So far I’ve been unable to identify the small sharks teeth found in the Holz Shale, but I was fortunate in being able to match the other specimens with the scientific and common names on record. I hope that this fossil site is still available for amateur paleontologists and collectors, but Orange County, California, is becoming cluttered with housing tracks and industrial property. Alas, after living in North Texas awhile, I am chagrined to discover the same phenomenon of urban growth.

Note: To zoom in and out, click on one of the photos below:

AMMONITES FROM THE HOLZ SHALE

In the lowest

strata of the Holz shale of the Ladd Formation, I discovered two distinct types

of ammonites: subprionocyclus sp. and scaphite sp. When I did my research following my exploration of Silverado

Canyon, both of these members of the subclass Ammonoidea of Cephalopoda were

the only ones I found in the canyon and were the only ones in literature. There may have been many more

discovered later, but since I live in Texas now, it will have to be someone

else who finds new species. The

attached photo includes each member from the subclass in the sedimentary rock

in which they were found. Due to

the fragmentary nature of the Holz shale, I decided not to trifle with

them. There are, I learned, many

enthusiasts who prefer to see a fossil left in its matrix, and I have learned

the hard way how easy a specimen can shatter.

Note: To zoom in and out, click on one

the photo below:

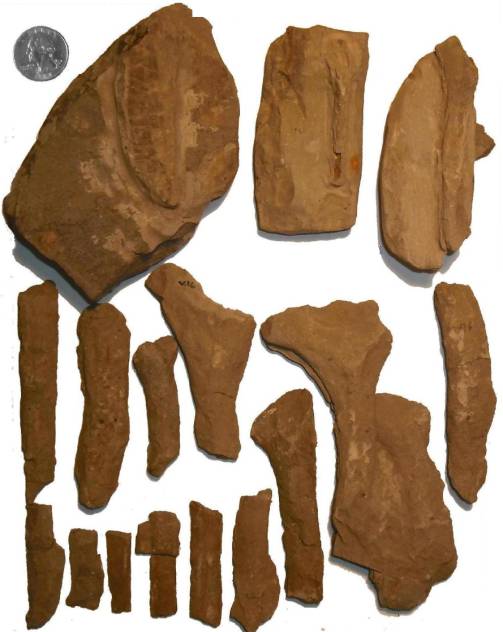

WORM BORROWS FROM THE HOLZ SHALE

Though they might look

like vertebrate fossils, I have been told that the fossils in this group are

probably worm burrows. If you look

closely, however, there is an uncanny resemblance to fossil teeth and

bone. Since I found them alongside

of fossil mollusks and sharks’ teeth in the Holz Shale, the opinions of other

fossil hunters is reasonable, and yet I’ve found from my research that even

paleontologists find it difficult to identify just exactly what species inhabit

such burrows.

Note: To zoom in and out, click the photo below:

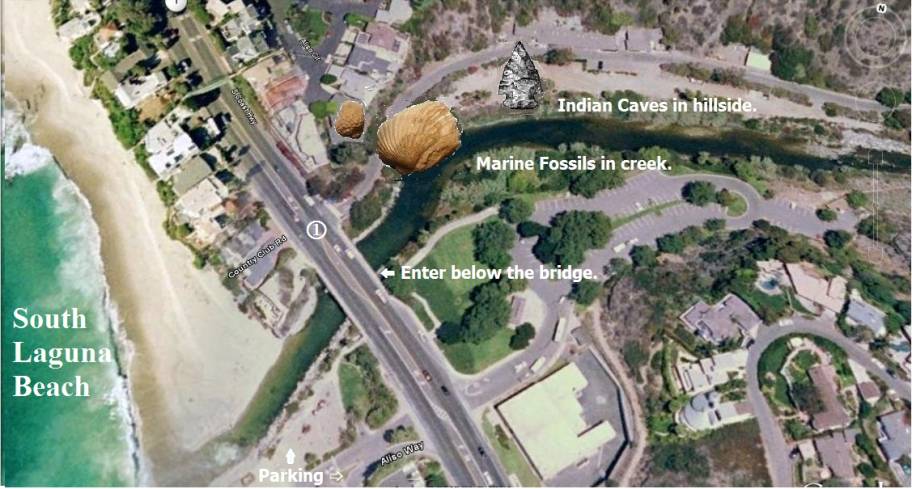

MARINE FOSSILS FROM SOUTH LAGUNA BEACH, CALIFORNIA

Awhile back when my wife and I lived in California,

we found a nice beach below the seaside city of Laguna Beach, California. On a whim, we decided to explore the

canyon nearby where a stream emptied into the Pacific. There were ancient

Native American caves on the sides of the canyon, containing kitchen middens,

charcoal (indicating fire pits), and pictographs on some of the cave walls. The University of California had labeled

these sites, so we cautiously explored the caves then moved up the canyon. It was then that we discovered what I

later identified, after research, as Upper Miocene clams and coral from the

Monterey Formation. The Indian

caves prickled my archeological side, but I would never disturb an

archeological site. My wife and I

left this out-of-the-way beach retreat with our paleontological treasures,

satisfied with our discovery of clams and coral fossils, but I wish I had taken

pictures of the caves, themselves.

Note: To zoom in and out, click the photo below:

|

|

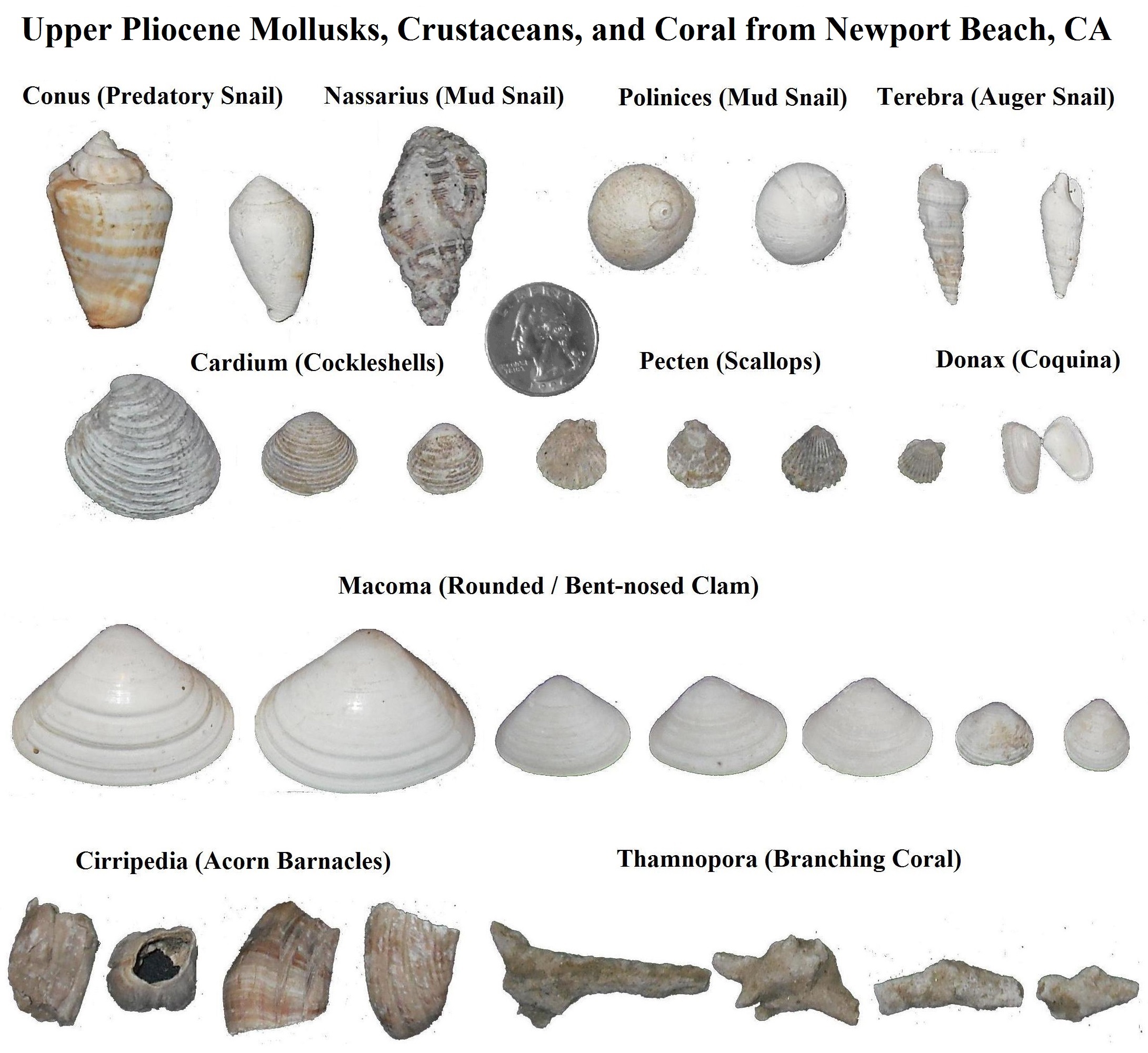

MARINE FOSSILS FROM NEWPORT BEACH, CALIFORNIA

In the Upper Pliocene Capistrano Formation, which

includes the Newport Beach area of Orange County, California, I discovered,

with several other fossil-hounds, a rich vein of marine fossils in the

sandstone and a few bird fossils in the mix. Because this outcrop was on private property, the club I

belonged to, led by a university paleontologist, was allowed to gather what was

tentatively identified by the scientist as Pleistocene fossils, but is now

considered to be Upper Pliocene, rather than Lower Pleistocene in age. The fossil mollusks, barnacles, and

coral in the photo are labeled with the scientific names for each genus with

the common name for each entry in parenthesis.

Note:

To zoom in and out, click the photo below: